by Rosie Dahlstrom, 2020

(https://rosiedahlstrom.wordpress.com/2020/08/19/on-andrea-rocha/)

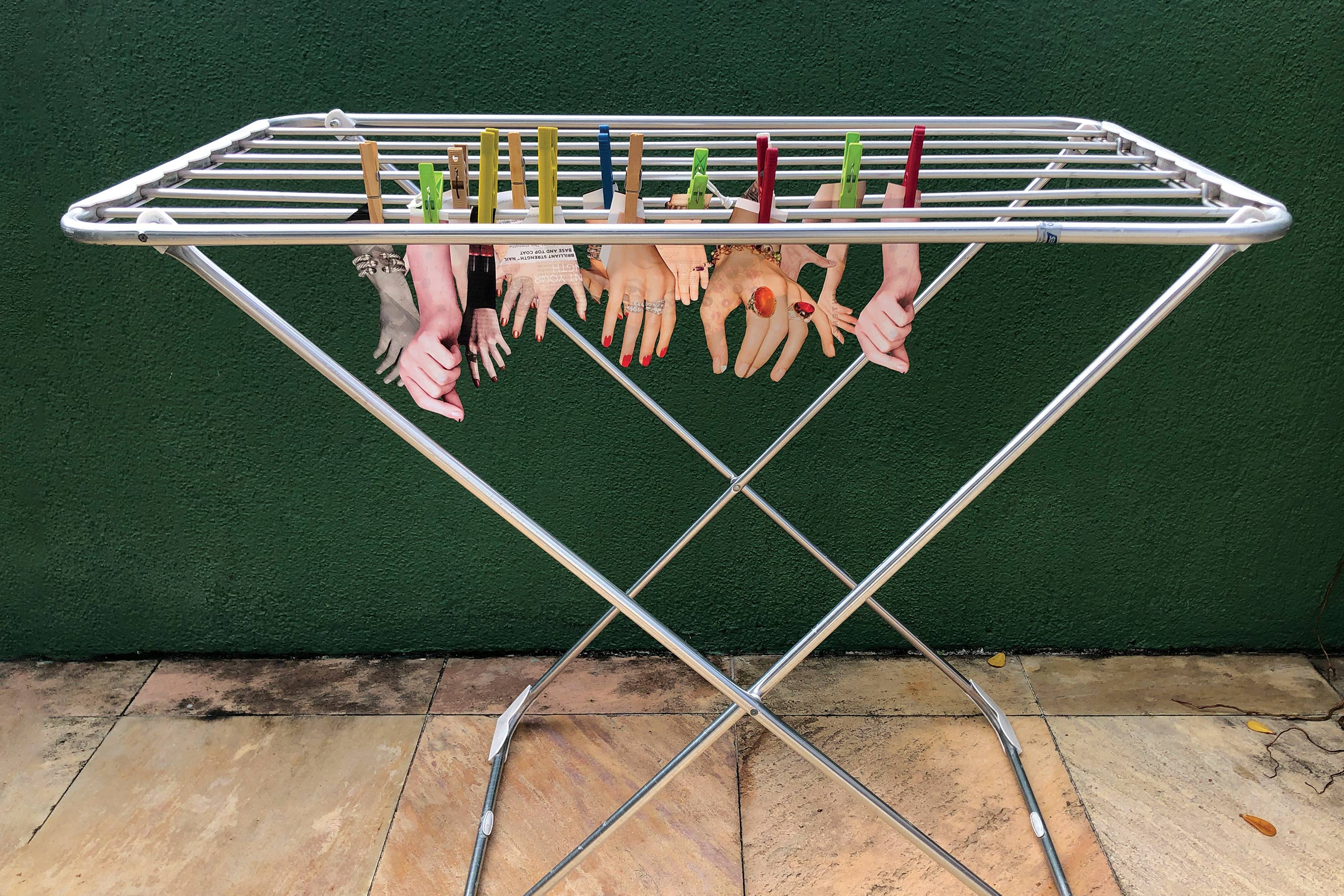

Fig. 1: ‘Wash Your Hands’, photographed collage, 2020

Two energies, or two competing forces, are at work in the photographic montages of Andrea Rocha (b. 1964, Rio de Janeiro). These warring visual phenomena, which we could refer to by what Sartre called the real and the ‘irreal’, come down to the manipulation of skin and paper in the collaged space of the artworks. Rocha, by turns across several projects, will either insert her own face into a glossy world of printed images, a real body attempting to become part of the photographic surface; or she brings images from the magazine pages into reality, in playful dioramas; paper dolls that try and escape into three-dimensional physicality.

A defining characteristic of Rocha’s imagery is a sense of unrest, restlessness. Fizzing, the eye flies whirring through weightless spaces with the energy of an out of control drone. The characters, shapes and surfaces of the image flit across constructed spatial dimensions, real space, internal space, pictorial space, and oscillate dizzily between scales and proportions. Life size, or doll size? As photographs of incidents, Rocha’s images induce the vertigo of the fabulous tales of an unreliable narrator.

In some sense, the space of the images does exist in the world or did at one time; physical pieces of paper did pose against each other like that, while insinuating a depth of fantastic space of the imagination, perhaps what comes before or after the scene, a narrative depth. Space is one indicator of the real, and time is the other. It is the temporal aspect that confirms the fiction of Rocha’s scenes. The time in Andrea’s images is frozen, the subjects are frozen in freeze-frame, frenetic movement, weightless like astronauts, timeless in their three-times-removed status from reality. Photographed, printed, selected, manipulated, and photographed and printed again.

Fig. 2: ‘Deep Dive’, photographed collage, 2011

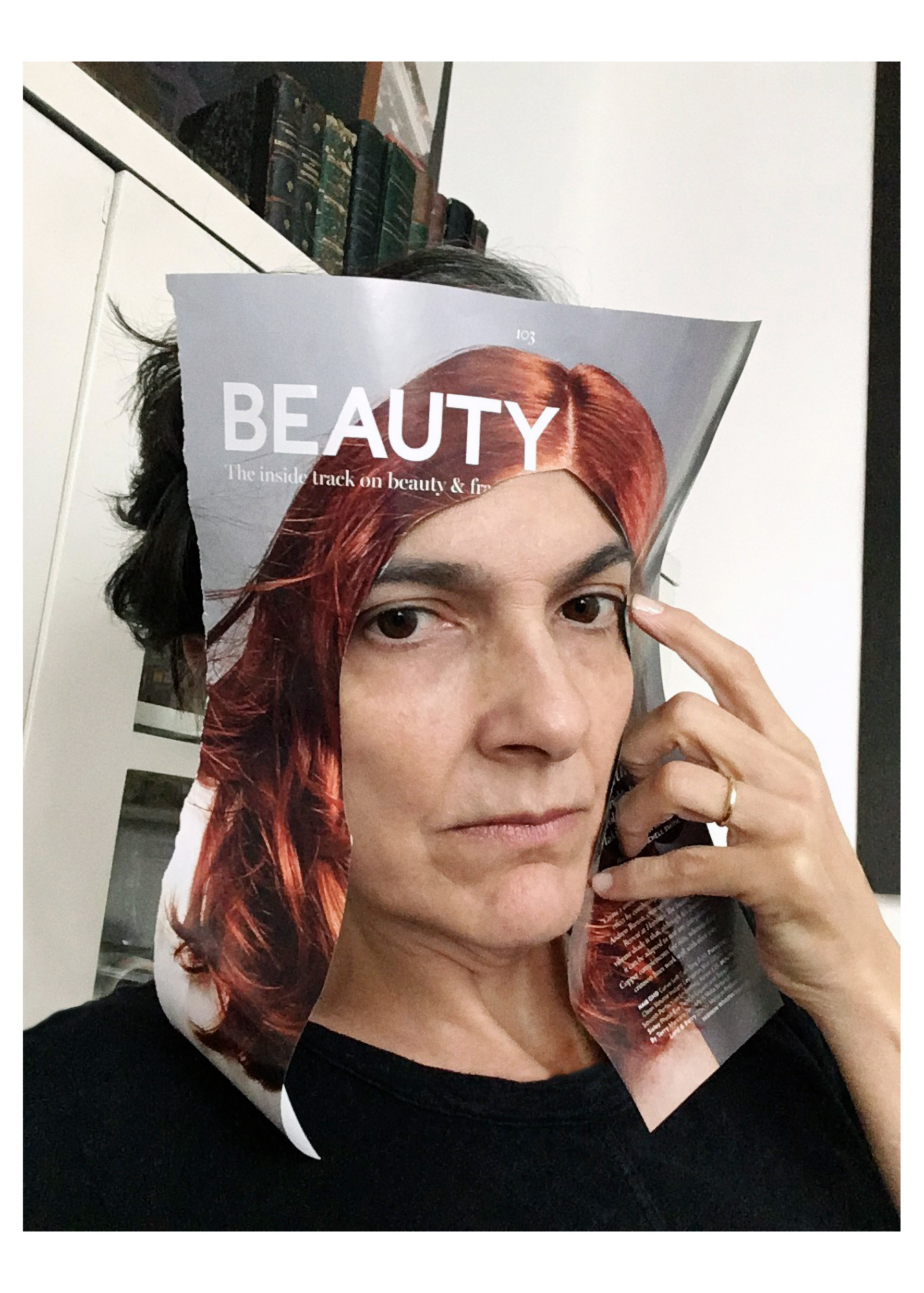

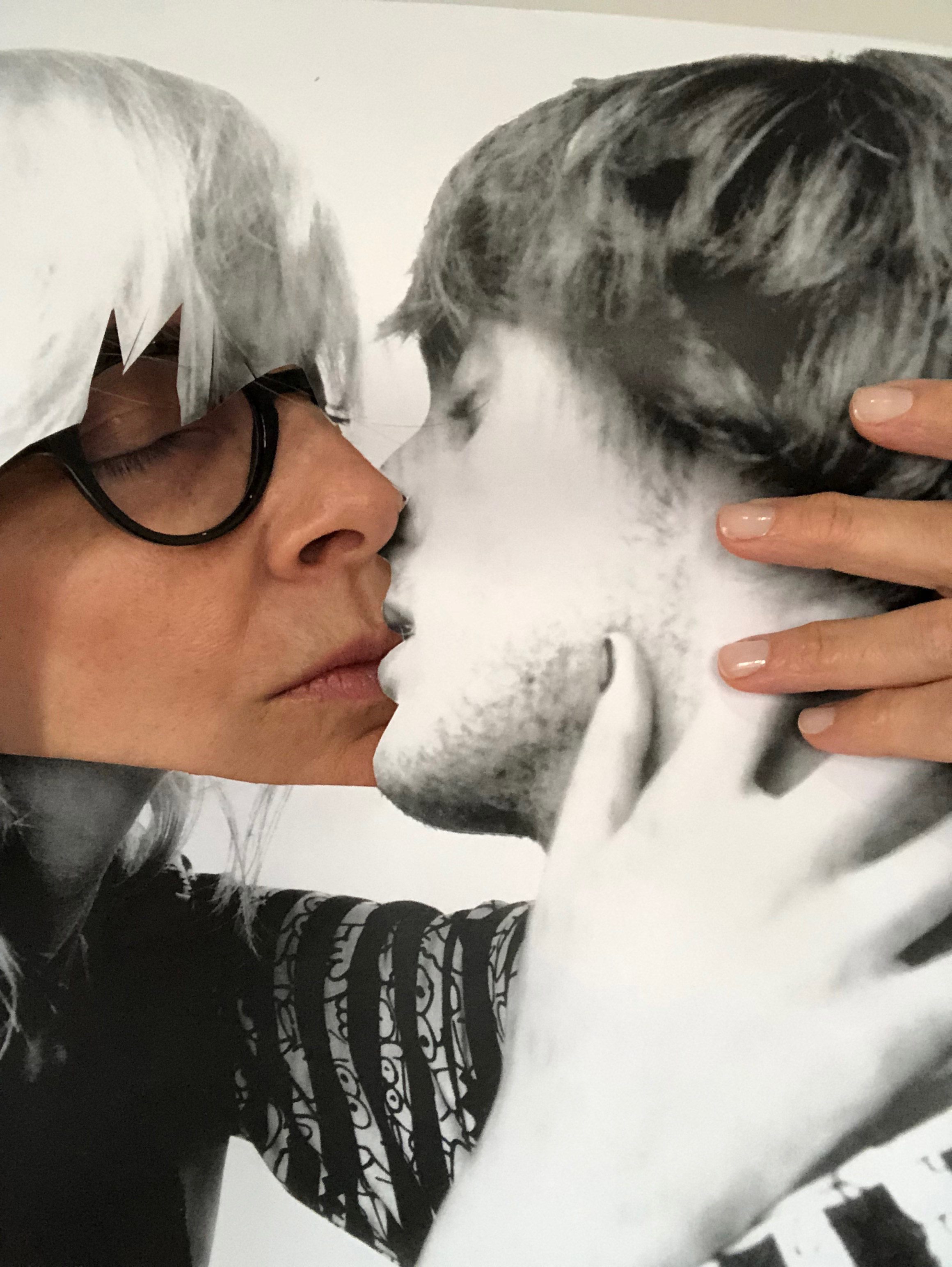

In Rocha’s earlier work (see Fig. 2), the glossy magazine paper surfaces of the collages evoke equally smooth and sleek textures; skin, fabric, hair, interiors. All is equal; the background setting anonymous, the models indistinguishable. A world that could be anywhere, populated by people who could be anyone. Only their irreverent combinations, provided with an occasional punchline in the form of wry titles, provide their purpose. A slight departure from this formula is Rocha’s subsequent ‘Selfie’ series (see Figs 3 and 4), combining the paper surface with the texture of her own skin; photographic image becomes an action and then turns back into image, moving between reality and fantasy; but most importantly creating, once more, a visual joke, an exercise in play.

The vast majority of Rocha’s work is beyond language, consisting of visual jokes that have no need of words, using instead the language of mass media, and perhaps glamour. As an artist with a past career as a translator, it is perhaps ironic that no translation is needed, no context is particularly required. Almost everyone in the world - or familiar with photographic media and advertising, amounting to the same thing at this point - will immediately understand the humour of her collages.

Fig. 3: ‘Self-Portrait no. 37’ and Fig. 4: ‘Self-Portrait no. 46’, from Fake Photoshop collage series, 2018-2019

There is another tension between the anonymity of the models in advertisements and the individuality of the artist’s face and hands. The purpose of the models is to sell; the purpose of Rocha is to mock. The construction of one’s identity involves one’s appearance, clothing, language, heritage, location, profession, a myriad of influences; the people suggested in Rocha’s scraps of paper have been posed, given their outfits to wear, or been divorced from their context; as a result they have no personality other than what Rocha gives them in the world of her work. In this way, the little paper cut-outs start to feel like co-conspirators, willing participants in the situations they find themselves in. When walking past her physical installations, the paper shapes will move and flutter (See Figs 5 and 6), adding a further impression of enthusiastic playing-along.

If identity is constructed out of your face, clothes, language, home, then Rocha’s work shows that all indicators of who you are can be broken down and reframed to tell a different story. At least, we shouldn’t take it all so seriously, when humour reveals so much about our identities.

“A reaction to a joke might come straight from the unconscious; reaction is also inevitably ideological. It can intimate a person’s background, family, education, income, class – yet, can’t be predicted. Some people can laugh at themselves, some can’t. Some see offence everywhere. Some look around to see if anyone else is laughing.”

Lynne Tillmans, ‘The Starkly Divisive Art of Contemporary Comedy’, Soft Skull Press, 2019

Fig. 5: ‘Run’ and Fig. 6: ‘Rescue Team’, installation shots of ‘Pulp Fiction’, 2019

As is apparent from the stacks of magazines Rocha tirelessly collects, the act of accumulating, magpie-like, images to be turned into vast collections is of primary importance in the artist’s process. Like the Fake Photoshop ‘selfie’ series, Rocha’s collection of found shopping lists reveal an obsession with unearthing something that gives the monolith of capitalism a human face. The shopping lists in their multitude, ordered and categorised, suggest a personal mark, handwriting, on the giant face of retail and supermarket commerce. They reveal patterns of gender, race and culture; they illuminate the most personal choices and preferences, like peeping through a stranger’s window.

The shopping lists collection, comprised again of abandoned pieces of paper (this time in supermarkets) is not always overtly shown in Rocha’s exhibition output, but it is easy to see under the surface: the collection brings together archaeology, collections, validity of archives, anthropology, voyeurism, obsession …

Of course, it is impossible to talk about supermarkets, or commerce of any kind without talking about waste. The environmental impact of the fashion industry alone is astonishing, then there is the automobile industry, again wrapped up in aspiration and identity, but a major polluter of recent years. Indeed, so much of our aspirational culture is built on ideas of rarity, individuality, when the reality is glamourous landfill. Rocha hates waste. She religiously reuses magazines that are free, otherwise headed for the bin, reusing and recycling, making use of a plentiful resource.

Fig. 7: ‘On Fire’ (2013), photographed paper collage, 2013

From a European perspective, and speaking purely in stereotypes, Brazil occupies a tense territory between first and third world country. On the forefront of the battle against climate change with its territory encompassing the Amazon rainforest, but also boasting decadent beach holiday destinations such as Rio, Rocha’s home city; known for Olympics-hosting, luxury tourism, hedonism, pornography, plastic surgery, but also huge wealth disparity, abuse of indigenous peoples and political controversy, dictatorships and abuses of power. An extreme country, whichever way one considers it. Rocha was born in the year that the military dictatorship seized power, a moment that has had a profound effect on all citizens that have lived through it. Recent developments with the current government - led by yet another terrifying man, Bolsonaro - have only cemented the image of Brazil as a country with a constantly tumultuous history (at least since 16th century Portuguese colonisation); as a country of extreme highs and lows: rich and poor, slum and beach, maids and millionaires.

I have of course been speaking of the first things that have come to mind, when considering Brazil and Rio, stereotypes, the language of mass media. The most interesting stereotype, however, when considering Rocha’s work and the context of her home, is the reputation of Rio as a city with one of the world’s highest rates of cosmetic surgeries and procedures; a city with ubiquitous and impossible beauty standards.

A cultural emphasis on one’s beauty has been imprinted on Rocha, as it must have been with all her contemporaries, since her earliest days. Another obsession, comparing her own appearance to beauty standards around her in an affluent, image-focussed society, where perhaps to be beautiful is to be normal. There are things we never really grow out of, though we can choose not to act on them; a fantasy of being beautiful - and therefore being powerful, desired, admired, listened to - is one that most girls will remember from their early childhood.

Perhaps this cutting and sticking with scissors and paper that Rocha has fixated on can be partly explained, though crudely, as childhood play that has re-emerged to form an art practice in later life. The manipulation of images can, if one relaxes their grip on reality as is easy for children (and perhaps artists), provide possible realisations of fantasies and mutations of restrictive identities. This idea of ‘play’ can be seen most clearly in what could be interpreted as paper dolls inhabiting elaborate dollhouses, all infused with that childlike animation of inanimate objects. Rocha enjoys creating these fictions but then occasionally breaking the fourth wall, by providing behind-the-scenes or ‘the making of’ information (see Figs 8 and 9), or by forcing the viewer to physically confront seductive images, highlighting their materiality.

Fig. 8: ‘Pritt Hopper’, and Fig. 9: the making of ‘Pritt Hopper’, photographed collage, 2011

The phrase ‘identity resistance’ taken from Rocha’s artist statement strikes as a particularly important motivation. Collage is clearly at the heart of Rocha’s identity as an artist; she will cut with her nails and teeth if her scissors are taken away, as she once dramatically told a lecturer who challenged her use of the medium. The images she creates depicting the forceful insertion of her body, face, personality, philosophy into the unbearable torrent of photographic images, advertisements and media that drown our vision as we move through the world, is a way of using identity as resistance. A victory of ‘me’ against ‘them’; a statement of insistence on my existence.

The most obvious body parts of Rocha’s in her work are, of course, her hands. She hand-cuts, hand-selects, hand-collects, hand-makes and hand-assembles everything she creates. She resists the digital, instead relying on her own ‘analogue Photoshop’ technique. You can sense her quick fingers tearing, cutting, sticking every fragment of paper on display; you feel her presence, her busy mind at work. She scours thousands of images, leafing through reams of paper, hunting for that satisfying, serendipitous combination that makes collage feel so effortless. The time, labour and dedication that goes into the making of a successful image just melt away. Resistance has become magic.